I am Mo Dexian, our home, I protect it. #GezhiTown#

Event Collection

Interview Collection

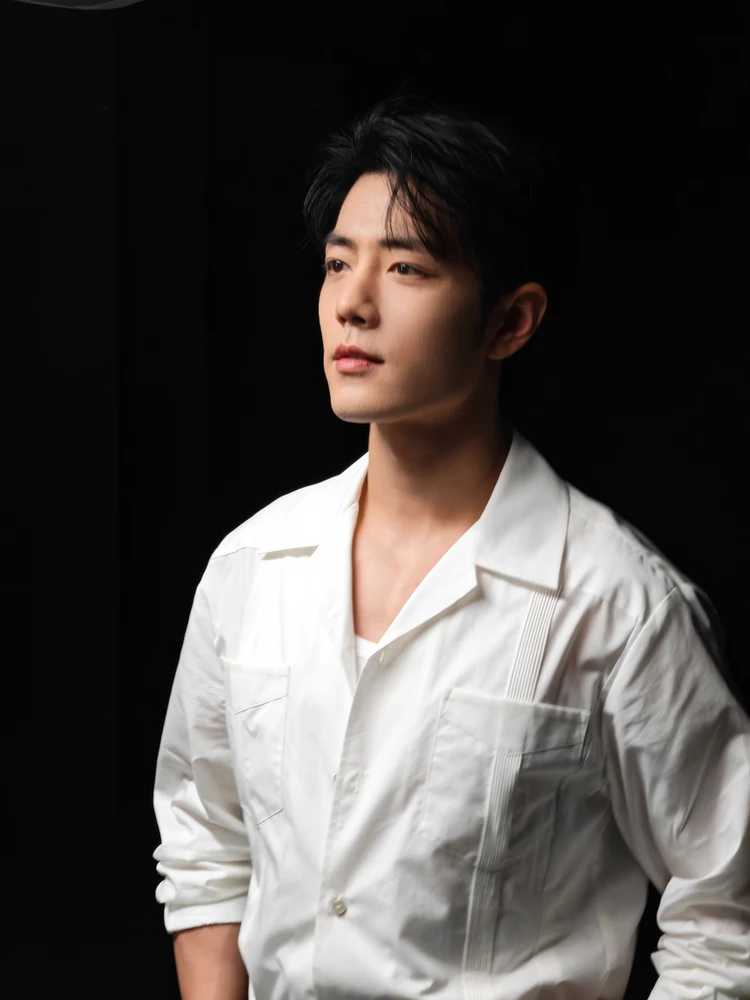

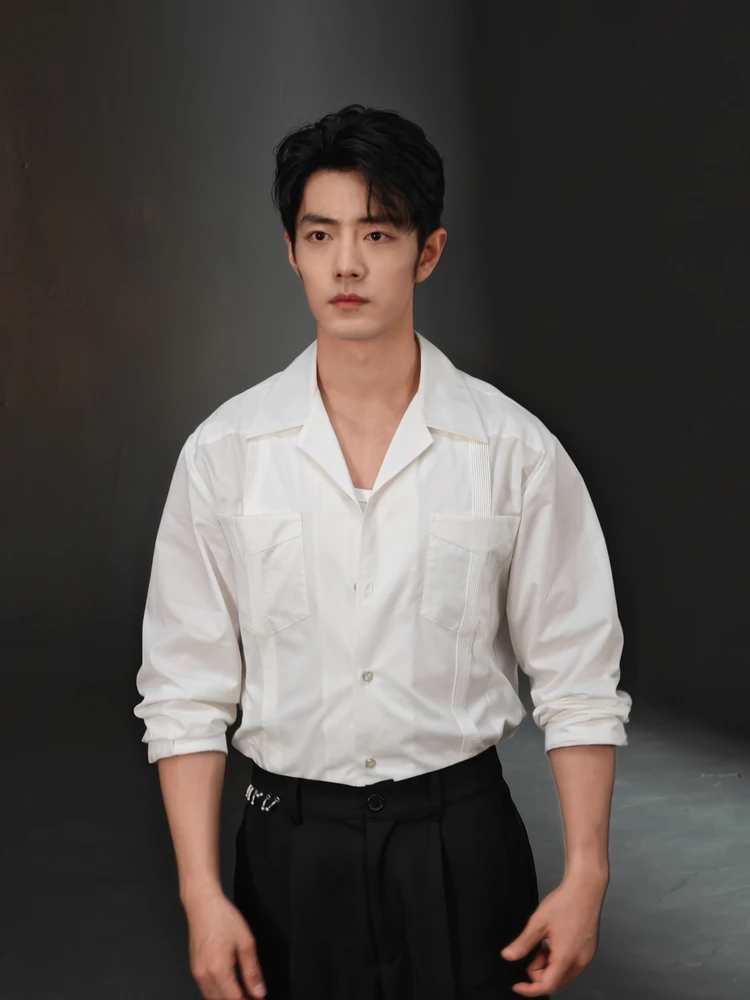

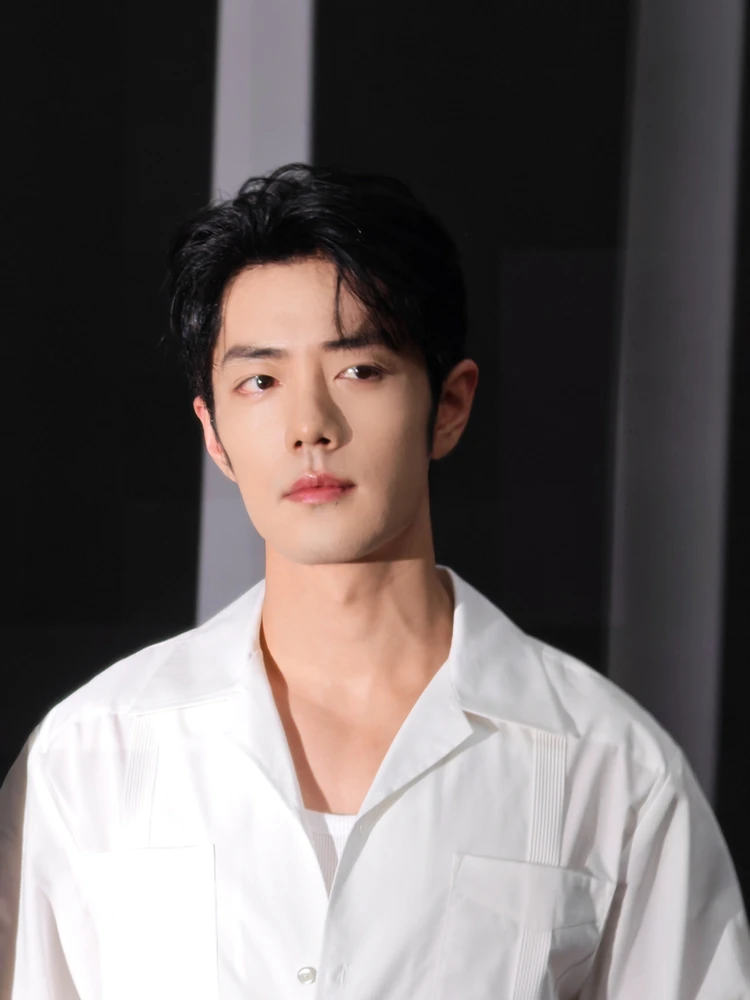

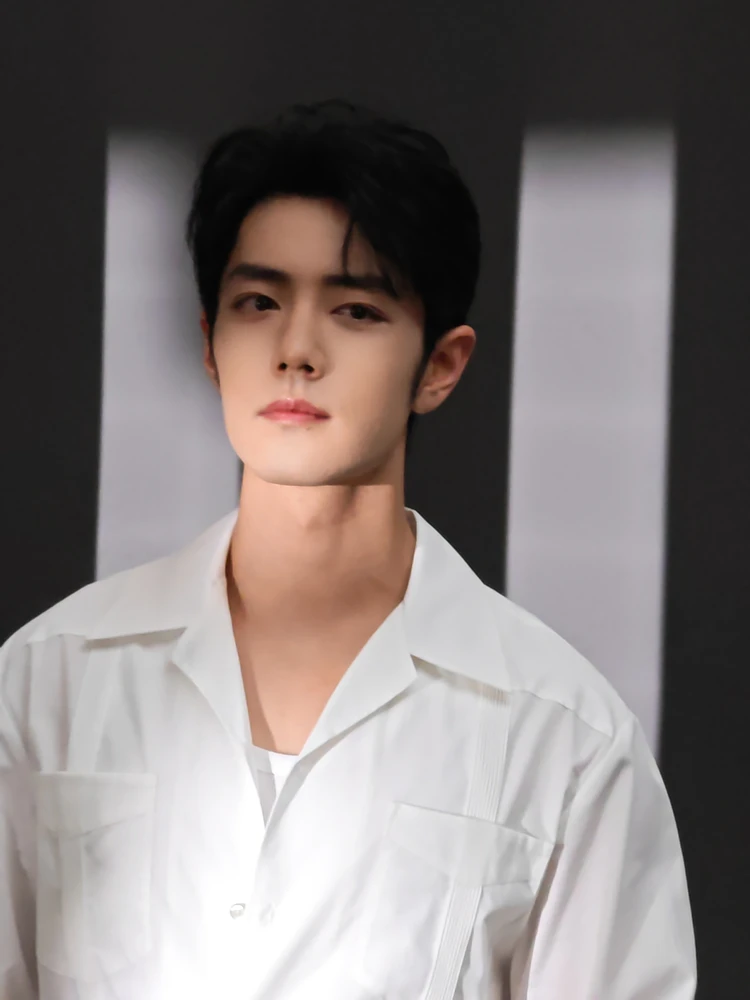

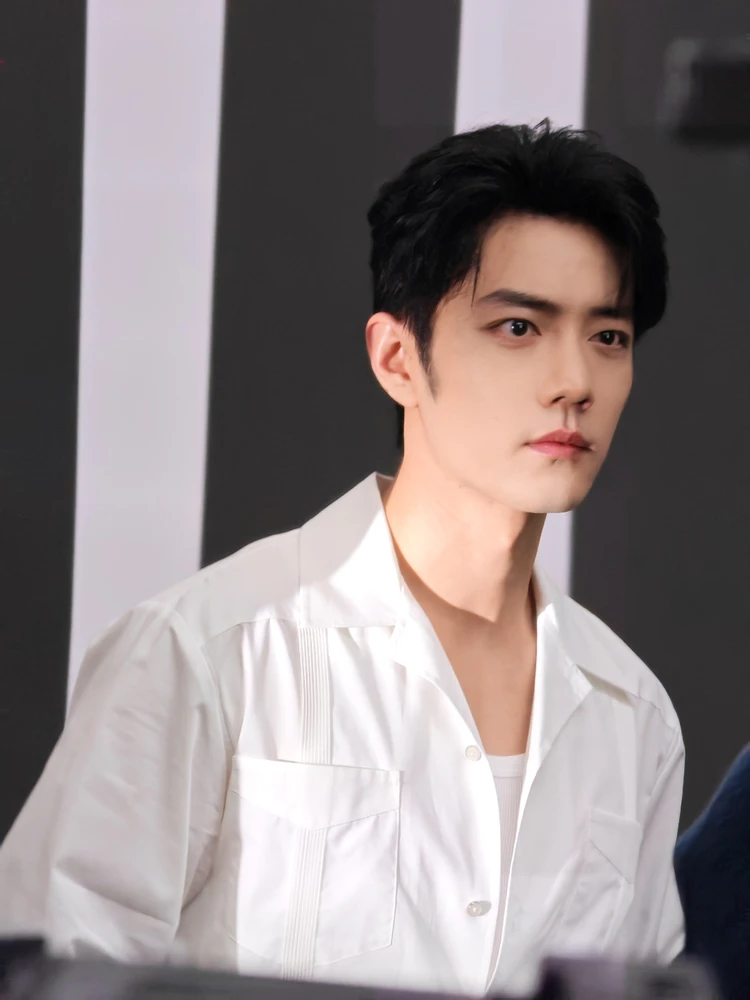

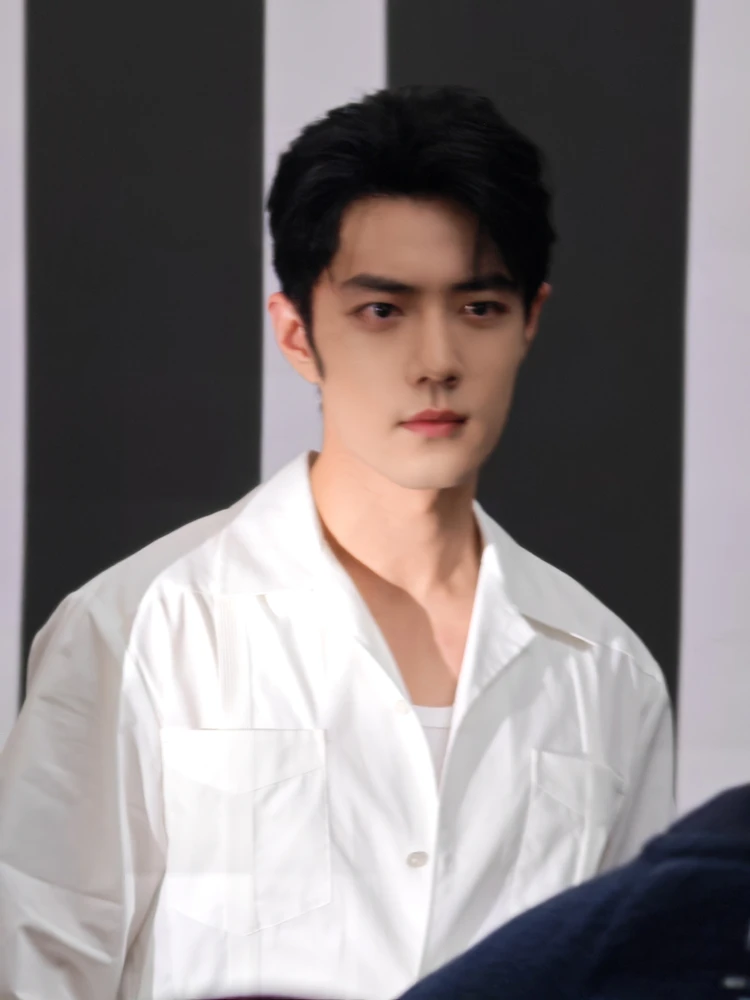

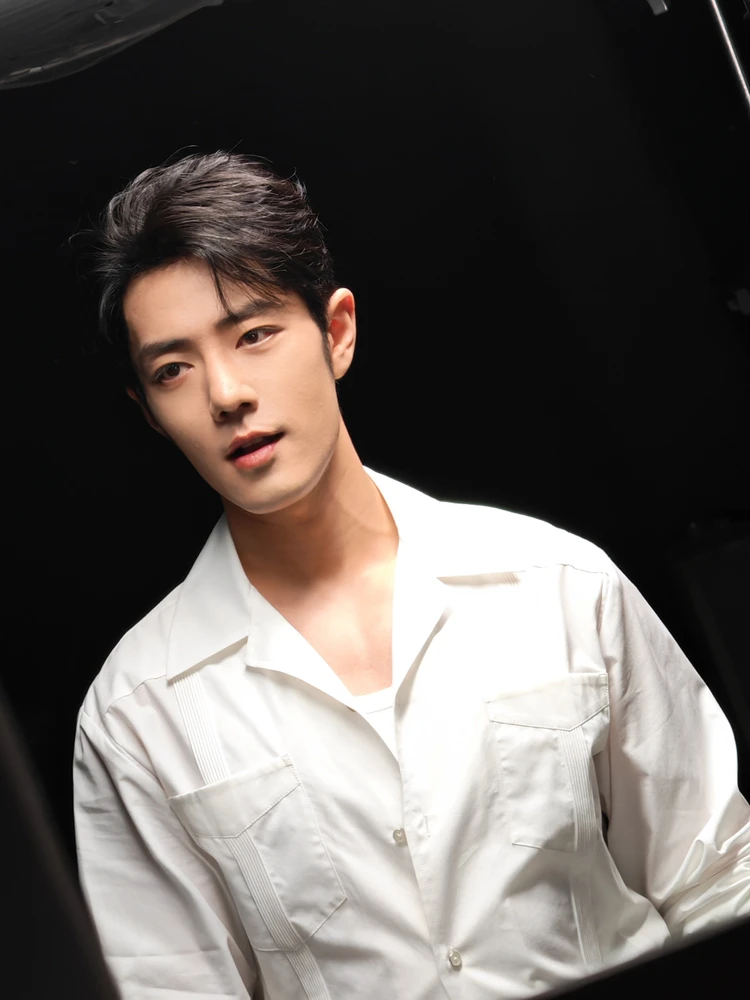

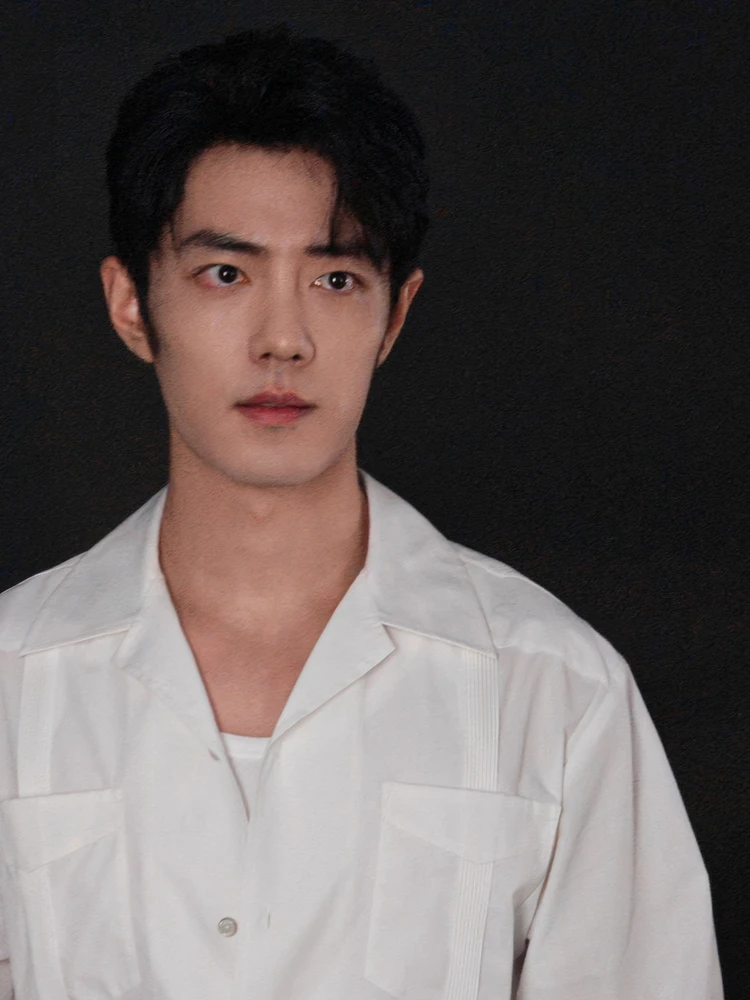

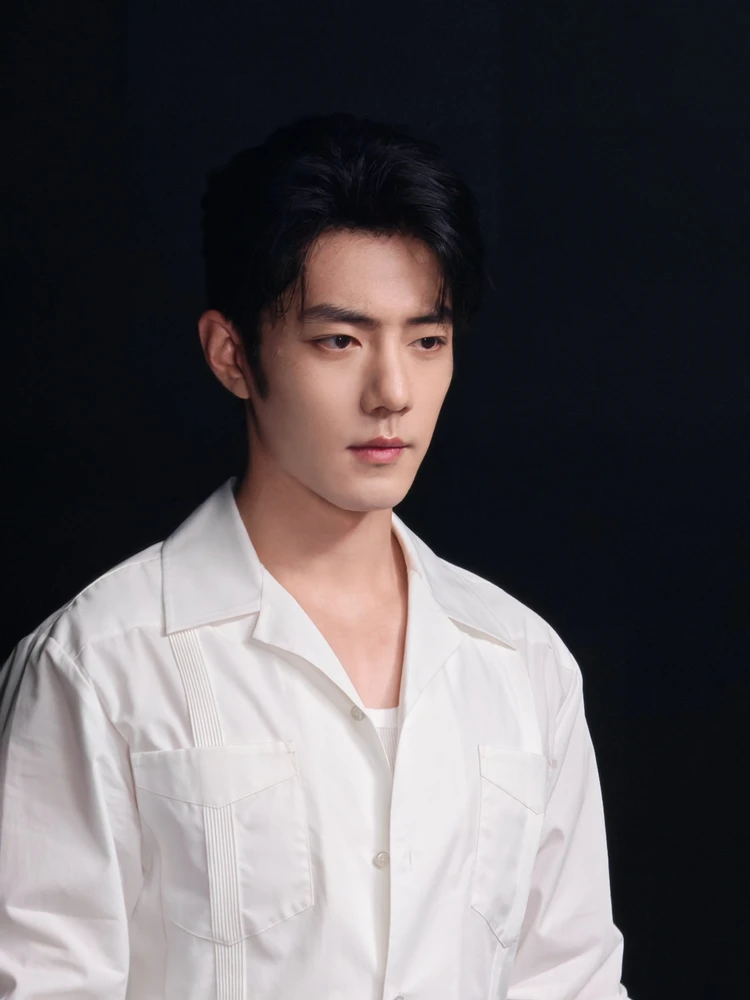

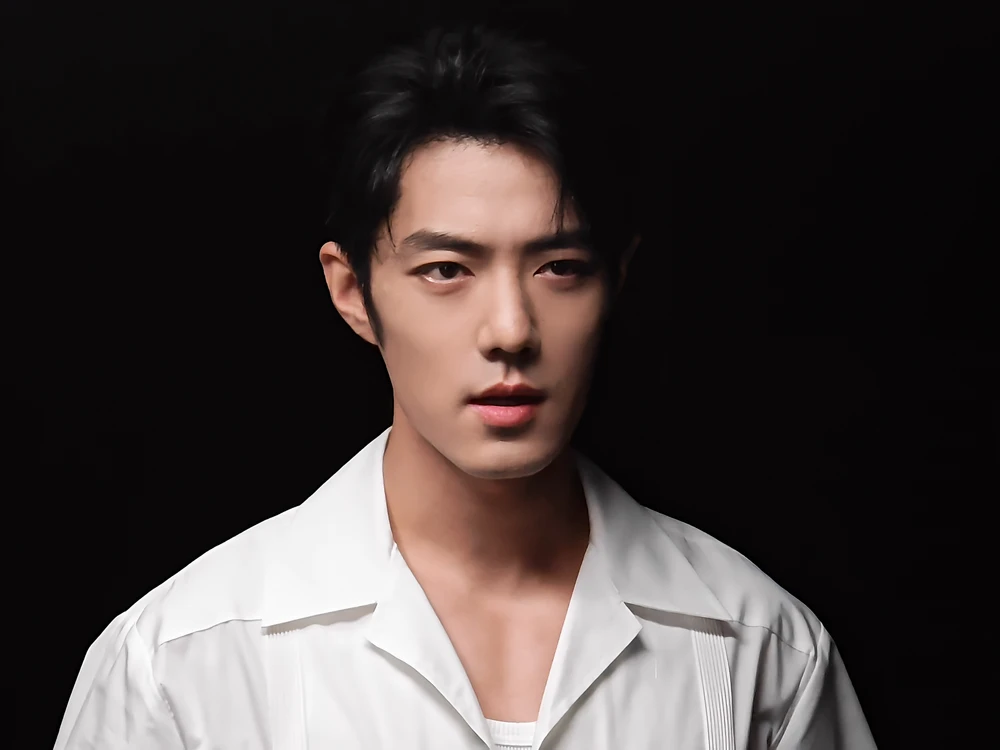

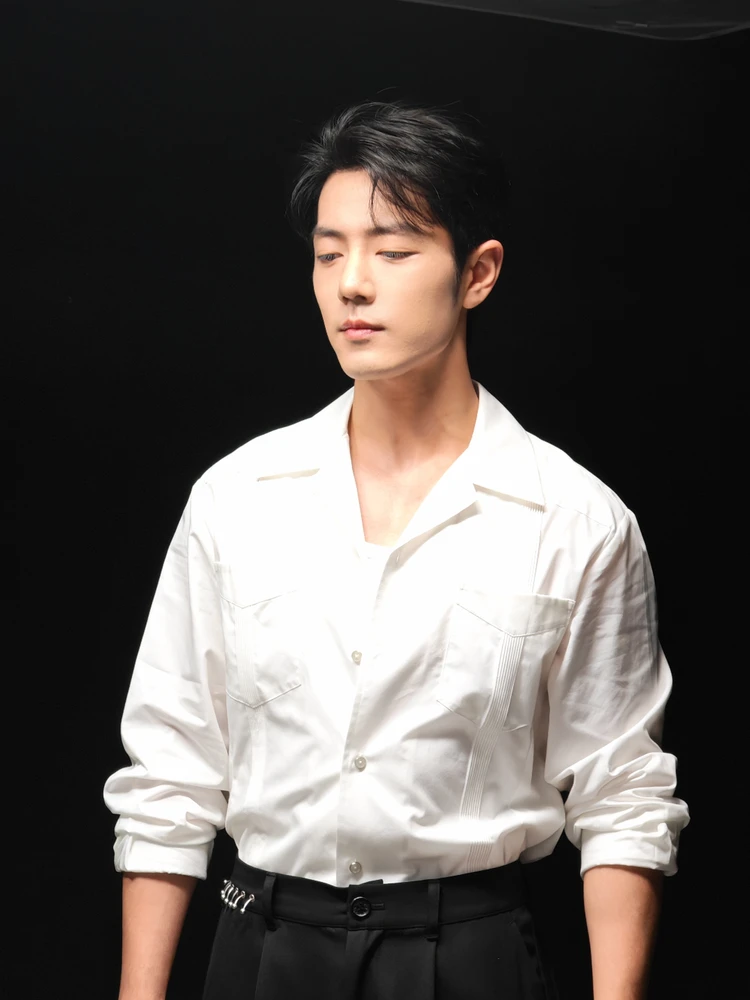

Mo Dexian

Actor Zhan

Editor’s Picks

2025/12/06 - by Gezhi Town/Xiao Zhan Studio

Gezhi Town Promotion Compilation

related posts:

Xiao Zhan

2025-12-06 19:54:19+0800

Xiao Zhan

2025-12-07 10:00:03+0800 发布于-

#GezhiTownMVExpressingTheBloodOfChineseYouth# With one body to face death, gathering the strength of the masses to fight against the enemy. The belief of guarding home stands firm, never retreating an inch! #GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in the theater!

央视新闻

2025-12-07 09:55:01+0800

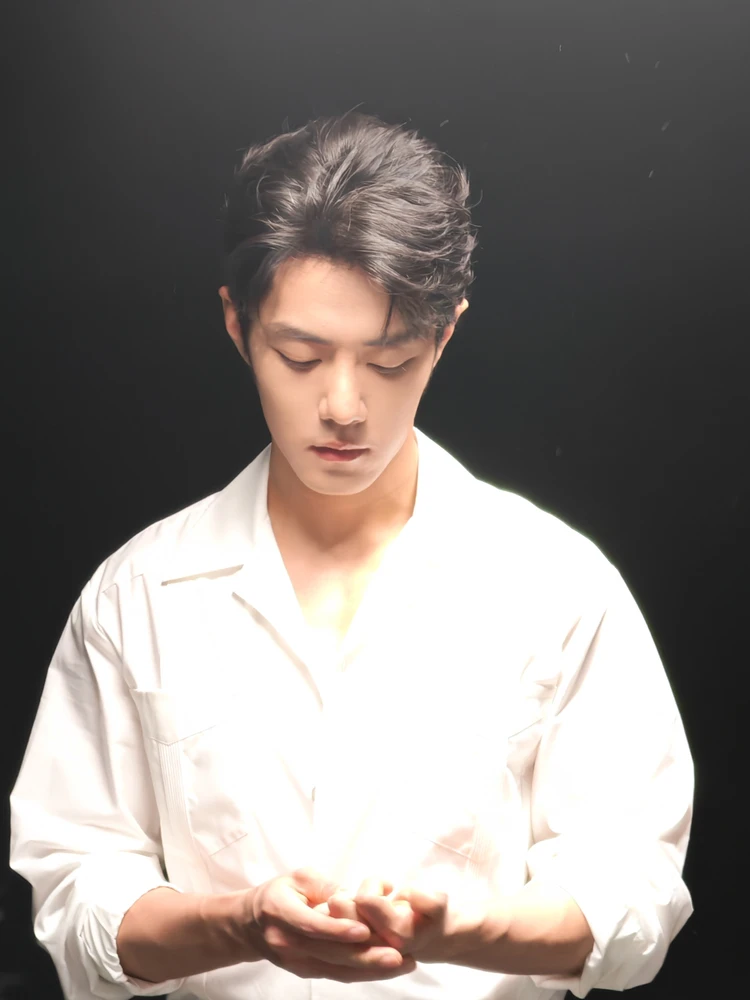

#GezhiTownMVExpressingTheResolveOfChinesePeople# @电影Gezhi Town officially released the theme song MV sung by @肖战, showcasing the transformation of ordinary people from seeking stability to rising up against enemies during the war of resistance. When the smoke of battle envelops the homeland, even though we are flesh and blood, we must uphold our beliefs and fight against the enemies! Salute to our predecessors! #GezhiTown# is now in theaters, see you there!

Xiao Zhan Studio

2025-12-08 11:30:11+0800

Listen to the indomitable cry, piercing through the artillery smoke, sharing moments of Mo Dexian @肖战 #GezhiTown# theme song MV!

Sina Movie

2025-12-09 14:31:53+0800

#XiaoZhanDebunksRumorsAboutInterningAtFactoryFor2MonthsForGezhiTown# The crew of 'Gezhi Town' @肖战 @彭昱畅 @周依然6 guest on Sina Entertainment's produced 'Yuqing Laboratory' trailer is here ![[点赞]](/images/weibo-emoji/点赞.png) Regarding the 'preparation for playing an 8th-grade mechanic', Xiao Zhan frankly stated that he watched a lot of materials and spent a long time in the props room, debunking the rumor that he interned at a factory for 2 months

Regarding the 'preparation for playing an 8th-grade mechanic', Xiao Zhan frankly stated that he watched a lot of materials and spent a long time in the props room, debunking the rumor that he interned at a factory for 2 months ![[干饭人]](/images/weibo-emoji/干饭人.png) , and also taught Zhou Yiran his规律 and心得 from blacksmithing

, and also taught Zhou Yiran his规律 and心得 from blacksmithing ![[抱一抱]](/images/weibo-emoji/抱一抱.png) Looking forward to more exciting content in the main film! #XiaoZhan'sHandsShowCallusesFromBothBlacksmithingAndFitness#

Looking forward to more exciting content in the main film! #XiaoZhan'sHandsShowCallusesFromBothBlacksmithingAndFitness#

![[点赞]](/images/weibo-emoji/点赞.png) Regarding the 'preparation for playing an 8th-grade mechanic', Xiao Zhan frankly stated that he watched a lot of materials and spent a long time in the props room, debunking the rumor that he interned at a factory for 2 months

Regarding the 'preparation for playing an 8th-grade mechanic', Xiao Zhan frankly stated that he watched a lot of materials and spent a long time in the props room, debunking the rumor that he interned at a factory for 2 months ![[干饭人]](/images/weibo-emoji/干饭人.png) , and also taught Zhou Yiran his规律 and心得 from blacksmithing

, and also taught Zhou Yiran his规律 and心得 from blacksmithing ![[抱一抱]](/images/weibo-emoji/抱一抱.png) Looking forward to more exciting content in the main film! #XiaoZhan'sHandsShowCallusesFromBothBlacksmithingAndFitness#

Looking forward to more exciting content in the main film! #XiaoZhan'sHandsShowCallusesFromBothBlacksmithingAndFitness#

China Movie Report

2025-12-09 22:01:01+0800

#XiaoZhanSaysMoDexian'sBottomLineIsToProtectFamilyAndHome# In the movie 'Gezhi Town', Xiao Zhan, starring as Mo Dexian, accepted an interview and shared his thoughts on playing the role: 'He is an iconic character with great significance. When his family and home are seriously threatened, crossing his bottom line, he must take up arms to defend them.'

China Movie Report

2025-12-09 22:01:01+0800

#XiaoZhanSaidMoDexianOftenSeeksInternalPeace# The movie 'Gezhi Town' stars Xiao Zhan, Peng Yuchang, and Zhou Yiran in an exclusive interview, deeply analyzing the inner trajectory of their characters. Xiao Zhan shares his insights on playing Mo Dexian: 'When his family and home are severely threatened, crossing his bottom line, he must take up arms to defend,' He also reveals the details of closing the eyes of Xiao Yan after his sacrifice during filming: 'I saw my hands were particularly dirty, so I wiped them on my chest before closing his eyes. This spontaneous reaction was included in the final cut by the director.'

Peng Yuchang interprets Xiao Yan: 'He is a person who cares about face, and under the influence of leisure, understands that merely avoiding is useless, completing his awakening and counterattack.' Zhou Yiran discusses her character Xia Cheng: 'She is simple; she just wants to live well with her family. As soon as she holds the baby, she has an instinctive maternal love, and she even developed skills to soothe the baby while filming.' She expresses, 'We are all ordinary people, but the strength that gathers together is very powerful. We do not provoke trouble and are not afraid of it.' #XiaoZhanSaidMoDexianWipedHisHandsBeforeClosingXiaoYan'sEyesWasImprovisedDesign##XiaoZhanSaidMoDexian'sBottomLineIsToProtectFamilyAndHome#

Peng Yuchang interprets Xiao Yan: 'He is a person who cares about face, and under the influence of leisure, understands that merely avoiding is useless, completing his awakening and counterattack.' Zhou Yiran discusses her character Xia Cheng: 'She is simple; she just wants to live well with her family. As soon as she holds the baby, she has an instinctive maternal love, and she even developed skills to soothe the baby while filming.' She expresses, 'We are all ordinary people, but the strength that gathers together is very powerful. We do not provoke trouble and are not afraid of it.' #XiaoZhanSaidMoDexianWipedHisHandsBeforeClosingXiaoYan'sEyesWasImprovisedDesign##XiaoZhanSaidMoDexian'sBottomLineIsToProtectFamilyAndHome#

China Movie Report

2025-12-09 22:01:01+0800

#XiaoZhanSaidMoDexianWipedXiaoYansEyesAsAnImpromptuDesign# In a special interview, movie 'Gezhi Town' starring Xiao Zhan reveals the details of closing Xiao Yan's eyes after his sacrifice: 'I saw my hands were particularly dirty, so I wiped them on my chest before closing his eyes. This spontaneous reaction was included by the director in the final cut.'

People's Daily

2025-12-10 09:09:41+0800

#TheCrossTemporalSceneInWarFilmsIsTearjerking# #XiaoZhanUnderstandsTheMeaningOfHomeThisWay# The movie 'Gezhi Town' is currently being screened. #People'sDailyOnLocationInterview# Conversations with director Kong Sheng, screenwriter Lan Xiaolong, and lead actor @肖战, telling the stories behind the scenes: When Xiao Zhan plays Mo Dexian shouting at the mountain, the long-distance shots are modern skyscrapers in Yichang, creating a huge contrast with the war-torn scenes that Mo Dexian faces in the film. This scene was once suggested by screenwriter Lan Xiaolong to be included in the final cut, which brought him to tears ↓↓

China Movie Report

2025-12-10 13:02:17+0800

#XiaoZhanTalkingToMoDexian# #XiaoZhanWantsToSayToMoDexianYouDidWell# Movie 'Gezhi Town' starring Xiao Zhan accepted an interview, remotely addressing the character 'Mo Dexian': 'Xiao Mo, as one of the countless descendants you mentioned, our lives are good and happy now, you did well.'

CCTV News

2025-12-11 15:10:41+0800

“#TheyNeverHadTimeHowDareWeForget#” #XiaoZhanMoDexianExperiencedThreeLosses# #XiaoZhanCCTVInterview# The movie 'Gezhi Town' is currently showing, showcasing the transformation of ordinary people during the Anti-Japanese War from seeking stability to rising up to resist the enemy. @肖战 plays the mechanic Mo Dexian, who experiences 'three losses' in the film and ultimately makes the choice to stand up for his 'home.' 'When there is no retreat, and hope is blocked, one must stand up to protect their homeland for themselves, their family, and their descendants.'

Speaking of the four characters 'Gezhi Town,' Xiao Zhan said he initially understood it as 'a meticulous production belonging to those with time,' but later gradually understood the weight behind it: 'De Xian is the name of the character, representing the people's longing for a stable life amidst the chaos of war; Jing Zhi reflects the artisan's requirement for the quality of craftsmanship, symbolizing the resilience and moral courage that countless ordinary people exhibit in times of desperation.' Xiao Zhan expressed that he wants to convey through the film that 'when there are concerns in the heart and responsibilities on the shoulders, there will be courage and determination to face challenges.'

Speaking of the four characters 'Gezhi Town,' Xiao Zhan said he initially understood it as 'a meticulous production belonging to those with time,' but later gradually understood the weight behind it: 'De Xian is the name of the character, representing the people's longing for a stable life amidst the chaos of war; Jing Zhi reflects the artisan's requirement for the quality of craftsmanship, symbolizing the resilience and moral courage that countless ordinary people exhibit in times of desperation.' Xiao Zhan expressed that he wants to convey through the film that 'when there are concerns in the heart and responsibilities on the shoulders, there will be courage and determination to face challenges.'

Xinhua News Agency

2025-12-11 17:06:00+0800

“Full Version! #GezhiTownCreatorsDiscussCreationIntention#” #XiaoZhanTalksAboutMoDexian'sProtectionAndGrowth# The movie 'Gezhi Town' is currently in theaters, and a story of a 'small family' during turbulent times has touched countless viewers. The film is filled with details, as screenwriter Lan Xiaolong, director Kong Sheng, and leading actor @肖战 analyze and clarify the audience's curiosities, character growth, and transformation layer by layer. 'Protecting the thousands of small families forms our big family.' Click the video to hear them discuss character development and creation intention! #GezhiTownCreatorsInterview# Follow @新华社 and become a loyal fan (interact for 3 days within 30 days), repost this Weibo to enter a raffle for 50 movie tickets to 'Gezhi Town'!

Gezhi Town

2025-12-11 19:00:01+0800

#GezhiTown![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownDoubleJourneyOnScreenAndOff# On screen, they are the ordinary people who steadfastly protect their homes, hiding 'fighting for family' in every stand they take, supporting the weight of protection with their ordinary blood and bones; off screen, they gather in theaters with reverence for the work, heading towards a reunion with their characters. 'Gezhi Town' is a story of fighting for family and a journey of mutual dedication!

# #GezhiTownDoubleJourneyOnScreenAndOff# On screen, they are the ordinary people who steadfastly protect their homes, hiding 'fighting for family' in every stand they take, supporting the weight of protection with their ordinary blood and bones; off screen, they gather in theaters with reverence for the work, heading towards a reunion with their characters. 'Gezhi Town' is a story of fighting for family and a journey of mutual dedication!

#GezhiTown# is currently in theaters, see you in the cinema!

![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownDoubleJourneyOnScreenAndOff# On screen, they are the ordinary people who steadfastly protect their homes, hiding 'fighting for family' in every stand they take, supporting the weight of protection with their ordinary blood and bones; off screen, they gather in theaters with reverence for the work, heading towards a reunion with their characters. 'Gezhi Town' is a story of fighting for family and a journey of mutual dedication!

# #GezhiTownDoubleJourneyOnScreenAndOff# On screen, they are the ordinary people who steadfastly protect their homes, hiding 'fighting for family' in every stand they take, supporting the weight of protection with their ordinary blood and bones; off screen, they gather in theaters with reverence for the work, heading towards a reunion with their characters. 'Gezhi Town' is a story of fighting for family and a journey of mutual dedication!#GezhiTown# is currently in theaters, see you in the cinema!

Xiao Zhan Studio

2025-12-12 11:10:58+0800

#GezhiTown# Mo Dexian @肖战 The story of fighting for home will be seen by everyone.

Gezhi Town

2025-12-12 11:00:01+0800

#GezhiTown![[超话]](/images/weibo-emoji/超话.png) # #XiaoZhanMomentsofTears# At the movie premiere, the audience deeply empathized with the character 'Mo Dexian' played by @肖战 and expressed heartfelt encouragement, moving the lead Xiao Zhan to tears on stage. This heartfelt empathy showcases the warmth of humanity, which will surely unleash tremendous power.

# #XiaoZhanMomentsofTears# At the movie premiere, the audience deeply empathized with the character 'Mo Dexian' played by @肖战 and expressed heartfelt encouragement, moving the lead Xiao Zhan to tears on stage. This heartfelt empathy showcases the warmth of humanity, which will surely unleash tremendous power.

#GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in theaters!

![[超话]](/images/weibo-emoji/超话.png) # #XiaoZhanMomentsofTears# At the movie premiere, the audience deeply empathized with the character 'Mo Dexian' played by @肖战 and expressed heartfelt encouragement, moving the lead Xiao Zhan to tears on stage. This heartfelt empathy showcases the warmth of humanity, which will surely unleash tremendous power.

# #XiaoZhanMomentsofTears# At the movie premiere, the audience deeply empathized with the character 'Mo Dexian' played by @肖战 and expressed heartfelt encouragement, moving the lead Xiao Zhan to tears on stage. This heartfelt empathy showcases the warmth of humanity, which will surely unleash tremendous power.#GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in theaters!

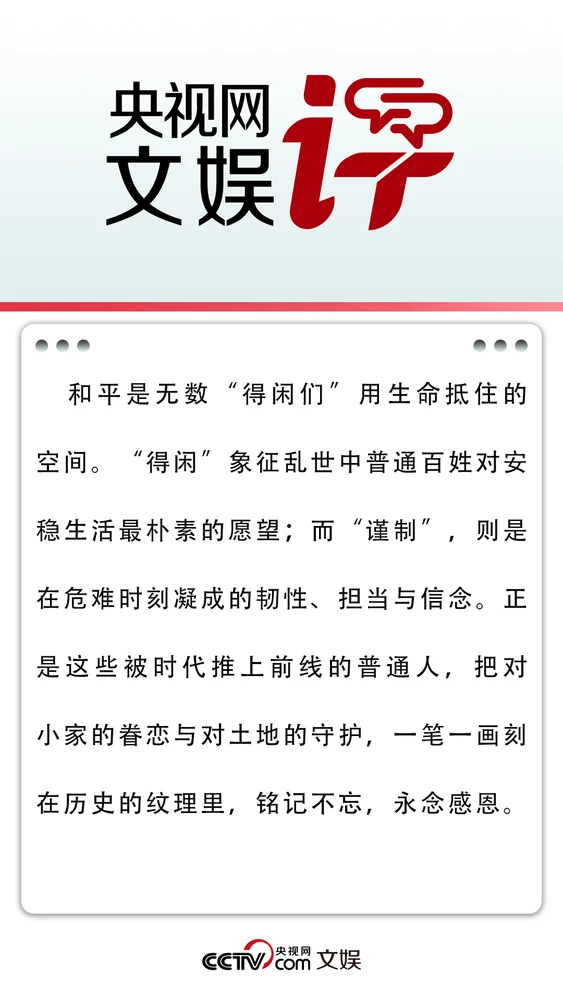

CCTV Entertainment

2025-12-12 12:00:00+0800

#CCTVEntertainmentReviewGezhiTown#: Expressing wishes through leisure, forging souls through caution

The war theme films we are familiar with mostly focus on grand battles, while 'Gezhi Town' takes a micro perspective to focus the lens on ordinary people in the midst of war, expressing the brutal essence of warfare. The film captures the instinctive reactions and survival choices of ordinary people amid the smoke of gunfire, probing the bottom line of human nature and spiritual resilience in the context of war.

The most shocking power of the film comes from the real deconstruction of ordinary people rather than heroism. Mo Dexian, Xiao Yan, Xia Cheng, and other residents of Gezhi Town, when faced with the invaders' bullets and cannon fire, first react with fear and helplessness—this is the most genuine shrinkage of life in the face of war. The film candidly presents the complexity of human nature in war: even when loved ones suffer, and hatred is etched deep, when it truly comes to drawing a knife and pulling the trigger, ordinary people still hesitate. They are the humble people who only rise from the ashes after their ordinary daily lives are utterly torn apart and their survival bottom lines are ruthlessly trampled. However, their original intention is simply to guard the most basic wish—to survive.

The core that supports the people and the artillery team from fleeing to guarding is the concept of 'home' that runs throughout the film. The opening's departure from home is the helplessness of 'home' being destroyed by war; the brief stop at Gezhi Town is a glimmer of trying to rebuild a 'new home'. However, when the invaders enter the town to massacre, they realize that fleeing does not bring real peace, and only resistance can retain the last glimmer of hope for 'home'. The film's interpretation of 'home' is hidden in countless details: the ancestral tablets carried by the elderly always represent the safeguarding of family lineage and the remembrance of homeland; Xia Cheng locking the collapsed door is the last obsession of ordinary people with 'home still existing'; the repeated appearance of pigs in the film subtly corresponds to the image of '家' hidden under the '宀' of 'home', deeply binding 'home' with the most basic survival resources and living scenes. These construct a simple yet profound cognition: the people's resistance stems from the ultimate protection of the 'small home', and this natural sublimation from 'protecting the small home' to 'guarding the big home' makes the motivation for national resistance more genuine, allowing 'patriotism' to become a tangible life belief.

The symbolic techniques and detailed designs in the film further reflect the helplessness and choices of ordinary people in the fire of war. The townspeople use rudimentary tools to resist regular armed forces, Mo Dexian sharpens his wife's kitchen knife to an incredible sharpness, and the elderly's stubborn actions—seeming to carry a touch of absurdity and comedic tone, actually capture the spiritual strength of ordinary people in chaotic times: a kitchen knife can become a weapon to protect family, and farming tools are also equipment to defend life; the elderly's frail body also hides an indomitable will. This is a commitment to the dignity of life and a microcosm of the indestructible spirit of the Chinese nation. The film builds a complete 'small world' through details, their adherence to the 'small home' seems small but gathers into a powerful force to resist foreign invasion; their individual struggles seem ordinary yet inscribe the essence of the national spirit, history is carved by the steadfastness and resistance of countless ordinary people.

Peace is the space that countless 'leisurely people' resist with their lives. 'Leisure' symbolizes the simplest wish of ordinary people for a stable life in chaotic times; while 'caution' is the resilience, responsibility, and belief forged in times of crisis. It is precisely these ordinary people pushed to the front line by the times who inscribe their attachment to the small home and guardianship of the land into the textures of history, remembering and never forgetting, always thankful.

The war theme films we are familiar with mostly focus on grand battles, while 'Gezhi Town' takes a micro perspective to focus the lens on ordinary people in the midst of war, expressing the brutal essence of warfare. The film captures the instinctive reactions and survival choices of ordinary people amid the smoke of gunfire, probing the bottom line of human nature and spiritual resilience in the context of war.

The most shocking power of the film comes from the real deconstruction of ordinary people rather than heroism. Mo Dexian, Xiao Yan, Xia Cheng, and other residents of Gezhi Town, when faced with the invaders' bullets and cannon fire, first react with fear and helplessness—this is the most genuine shrinkage of life in the face of war. The film candidly presents the complexity of human nature in war: even when loved ones suffer, and hatred is etched deep, when it truly comes to drawing a knife and pulling the trigger, ordinary people still hesitate. They are the humble people who only rise from the ashes after their ordinary daily lives are utterly torn apart and their survival bottom lines are ruthlessly trampled. However, their original intention is simply to guard the most basic wish—to survive.

The core that supports the people and the artillery team from fleeing to guarding is the concept of 'home' that runs throughout the film. The opening's departure from home is the helplessness of 'home' being destroyed by war; the brief stop at Gezhi Town is a glimmer of trying to rebuild a 'new home'. However, when the invaders enter the town to massacre, they realize that fleeing does not bring real peace, and only resistance can retain the last glimmer of hope for 'home'. The film's interpretation of 'home' is hidden in countless details: the ancestral tablets carried by the elderly always represent the safeguarding of family lineage and the remembrance of homeland; Xia Cheng locking the collapsed door is the last obsession of ordinary people with 'home still existing'; the repeated appearance of pigs in the film subtly corresponds to the image of '家' hidden under the '宀' of 'home', deeply binding 'home' with the most basic survival resources and living scenes. These construct a simple yet profound cognition: the people's resistance stems from the ultimate protection of the 'small home', and this natural sublimation from 'protecting the small home' to 'guarding the big home' makes the motivation for national resistance more genuine, allowing 'patriotism' to become a tangible life belief.

The symbolic techniques and detailed designs in the film further reflect the helplessness and choices of ordinary people in the fire of war. The townspeople use rudimentary tools to resist regular armed forces, Mo Dexian sharpens his wife's kitchen knife to an incredible sharpness, and the elderly's stubborn actions—seeming to carry a touch of absurdity and comedic tone, actually capture the spiritual strength of ordinary people in chaotic times: a kitchen knife can become a weapon to protect family, and farming tools are also equipment to defend life; the elderly's frail body also hides an indomitable will. This is a commitment to the dignity of life and a microcosm of the indestructible spirit of the Chinese nation. The film builds a complete 'small world' through details, their adherence to the 'small home' seems small but gathers into a powerful force to resist foreign invasion; their individual struggles seem ordinary yet inscribe the essence of the national spirit, history is carved by the steadfastness and resistance of countless ordinary people.

Peace is the space that countless 'leisurely people' resist with their lives. 'Leisure' symbolizes the simplest wish of ordinary people for a stable life in chaotic times; while 'caution' is the resilience, responsibility, and belief forged in times of crisis. It is precisely these ordinary people pushed to the front line by the times who inscribe their attachment to the small home and guardianship of the land into the textures of history, remembering and never forgetting, always thankful.

Litchi News

2025-12-12 13:31:44+0800

“#GezhiTownisAFilmAboutResistanceForOrdinaryPeople# #XiaoZhanPortrayedTheNationalStrengthRepresentedByMoDexian#” Recently, the movie “Gezhi Town” is being screened. Liu Yongchang, a professor at Nanjing Normal University’s School of Journalism and Communication, stated that this does not appear to be a typical war-themed film. It lacks the grand war scenes filled with smoke and the stirring legends of heroes. It tells the story of ordinary people’s resistance—a group of common folks and a team of disbanded artillery soldiers, who ultimately defeat the enemy after making tragic sacrifices. This story obviously does not have corresponding historical records, and the stage of Gezhi Town is a dramatized setting, which gives the screenwriter and director more room for creativity. There is joy amid sorrow, and sorrow amid joy; the black humor sprinkled throughout the film is not particularly 'serious,' but it feels particularly sincere because its plot is built on the foundation of real human nature.

The search for a 'path' is the most important narrative thread in “Gezhi Town.” The first half of the film depicts the survival journey of the common people as they flee westward. A passenger ship filled with refugees drifts along the Yangtze River, setting the atmosphere of destruction and loss at the start of the war. Two years later in Yichang, the people hurriedly evacuate from their homes again, coinciding with the real historical event of the Yichang evacuation. When the people finally find 'Gezhi,' this small town of refuge, they think their lives can finally be peaceful, only to have everything shattered by the random intrusion of three Japanese soldiers.

The film does not overly dramatize the difficulties, bitterness, and pain of the survival journey. Instead, it continuously fills the screen with humor, such as the diving antics of a grandfather and grandson on the passenger ship becoming a comical twist of fate, followed immediately by the arrival of the 'ordinary' young master. In the town of Gezhi, the common people can joke with each other in their idyllic lives, while soldiers can play joyfully in the clear river waters. While ordinary citizens undoubtedly find it hard to have peace in turbulent times, as long as there is a glimmer of hope or a small gap, they will create every possibility for life. Thus, the protagonist Mo Dexian’s name acts as a dual metaphor: one, the endless displacement of people during the war, and two, the unwavering 'strength of life' of this nation that has persisted for thousands of years.

The child Mo Dexian's name naturally comes from Yue Fei's 'Man Jiang Hong' line, 'Don’t wait idly, hair turning grey in youth, empty sadness,' signifying a determined struggle and an unyielding fight. In the beginning, people have been fleeing, seeking survival, and when there is truly no escape, they are forced to fight back. The narrative regarding the path of resistance in the second half of the film suddenly becomes tense, with one side representing the Japanese army's covetousness, invasion, and massacre, while the other represents the citizens defending their homeland, creating a strong contrast that fills the story with dramatic tension. The once beautiful 'Gezhi' town turns into a cruel 'Wu' town, where peace and war transition in an instant.

Gezhi Town has alleys, mountain walls, and sturdy houses; it is a complex and perilous battlefield deliberately designed. On our side, we have panicking civilians and a ragtag artillery unit, as well as the spiritual 'leader' Mo Dexian who has grown in the fires of war, and a Swiss-made Su Lu Tong cannon that survives catastrophe. On the enemy side, there are three brutal Japanese soldiers, then a tank rampaging and a team of soldiers going on a rampage. Because the structure is simple, the stage will focus; because the clues are clear, the narration will be unhurried.

The film’s combat visuals are splendid, showcasing guerrilla-style intrusions, open attacks and ambushes, soldiers and civilians, the back-and-forth struggles and sudden attacks are breathtaking; there are positional battles where a tank and an artillery piece remain evenly matched—this seems illogical but captivating, ultimately leading to the climax of the battle. Continuous fighting itself is obviously not the focus of the film’s expression, so the narrator often uses distancing techniques to divert the audience’s attention. For example, the random drifting of great-grandfather and grandson on the battlefield, the teasing between 'teammates' during intense fighting, and the exaggerated and artificial performances of the Japanese soldiers, even the intermittent appearances of a pig and a sheep, all seem to deconstruct the 'professionalism' of the battle to some degree. These scenes temporarily alleviate the audience's tension, and in the moments of tension and relaxation, they make the audience realize the narrator’s focus: it is about people, not the battle.

Such life-and-death scenes are certainly the best for highlighting character images—only in desperate situations can the complex facets of humanity be completely revealed. Mo Dexian, a minor employee at the Jinling Arsenal, lives a comfortable life in Gezhi Town due to his 'craftsman spirit,' but when the aggressors tighten the noose, he is the first to rise in rebellion—the flagpole hiding explosives serves as a metaphor, as he resolutely begins to fight. The captain of the artillery unit, Xiao Yan, who has always shown weakness and anxiety due to the psychological trauma of war, finally rises to become a true gunner who sacrifices himself beside his comrades. Picking up a kitchen knife, raising a firearm, drawing a bow, in Gezhi Town, there is no distinction between civilians and soldiers; nearly everyone is fighting. In the film, every owner of Gezhi Town is imperfect and has lovable or detestable flaws; most of the time they are ordinary and humble, only seeking to live their lives. Such character portrayal is actually more powerful; ordinariness is the norm, thus the extraordinary resistance and sacrifice is even more moving.

Strictly speaking, the victory logic of Gezhi Town appears overly simplistic. In contrast, the film’s portrayal of the enemy is largely caricatured. The Japanese soldiers are cruel, creating hell on earth, but how could they be that foolish? The various 'foolish' actions of enemies in the film are more to satisfy the audience’s pleasure, so a well-supplied Su Lu Tong cannon barely becomes a note of victory in battle. However, looking at it from another perspective, the victory logic of Gezhi Town is reasonable because it reflects the victory logic of the Chinese people in the War of Resistance. An individual's struggle may be powerless, a small town's struggle may be in vain, but the collective struggle of a continuously thriving great nation is full of strength. This is the most touching metaphor of “Gezhi Town.” #XiaoZhan![[超话]](/images/weibo-emoji/超话.png) # (The author is the Vice Chairman of the Jiangsu Province Television Artists Association and a professor at Nanjing Normal University’s School of Journalism and Communication)

# (The author is the Vice Chairman of the Jiangsu Province Television Artists Association and a professor at Nanjing Normal University’s School of Journalism and Communication)

The search for a 'path' is the most important narrative thread in “Gezhi Town.” The first half of the film depicts the survival journey of the common people as they flee westward. A passenger ship filled with refugees drifts along the Yangtze River, setting the atmosphere of destruction and loss at the start of the war. Two years later in Yichang, the people hurriedly evacuate from their homes again, coinciding with the real historical event of the Yichang evacuation. When the people finally find 'Gezhi,' this small town of refuge, they think their lives can finally be peaceful, only to have everything shattered by the random intrusion of three Japanese soldiers.

The film does not overly dramatize the difficulties, bitterness, and pain of the survival journey. Instead, it continuously fills the screen with humor, such as the diving antics of a grandfather and grandson on the passenger ship becoming a comical twist of fate, followed immediately by the arrival of the 'ordinary' young master. In the town of Gezhi, the common people can joke with each other in their idyllic lives, while soldiers can play joyfully in the clear river waters. While ordinary citizens undoubtedly find it hard to have peace in turbulent times, as long as there is a glimmer of hope or a small gap, they will create every possibility for life. Thus, the protagonist Mo Dexian’s name acts as a dual metaphor: one, the endless displacement of people during the war, and two, the unwavering 'strength of life' of this nation that has persisted for thousands of years.

The child Mo Dexian's name naturally comes from Yue Fei's 'Man Jiang Hong' line, 'Don’t wait idly, hair turning grey in youth, empty sadness,' signifying a determined struggle and an unyielding fight. In the beginning, people have been fleeing, seeking survival, and when there is truly no escape, they are forced to fight back. The narrative regarding the path of resistance in the second half of the film suddenly becomes tense, with one side representing the Japanese army's covetousness, invasion, and massacre, while the other represents the citizens defending their homeland, creating a strong contrast that fills the story with dramatic tension. The once beautiful 'Gezhi' town turns into a cruel 'Wu' town, where peace and war transition in an instant.

Gezhi Town has alleys, mountain walls, and sturdy houses; it is a complex and perilous battlefield deliberately designed. On our side, we have panicking civilians and a ragtag artillery unit, as well as the spiritual 'leader' Mo Dexian who has grown in the fires of war, and a Swiss-made Su Lu Tong cannon that survives catastrophe. On the enemy side, there are three brutal Japanese soldiers, then a tank rampaging and a team of soldiers going on a rampage. Because the structure is simple, the stage will focus; because the clues are clear, the narration will be unhurried.

The film’s combat visuals are splendid, showcasing guerrilla-style intrusions, open attacks and ambushes, soldiers and civilians, the back-and-forth struggles and sudden attacks are breathtaking; there are positional battles where a tank and an artillery piece remain evenly matched—this seems illogical but captivating, ultimately leading to the climax of the battle. Continuous fighting itself is obviously not the focus of the film’s expression, so the narrator often uses distancing techniques to divert the audience’s attention. For example, the random drifting of great-grandfather and grandson on the battlefield, the teasing between 'teammates' during intense fighting, and the exaggerated and artificial performances of the Japanese soldiers, even the intermittent appearances of a pig and a sheep, all seem to deconstruct the 'professionalism' of the battle to some degree. These scenes temporarily alleviate the audience's tension, and in the moments of tension and relaxation, they make the audience realize the narrator’s focus: it is about people, not the battle.

Such life-and-death scenes are certainly the best for highlighting character images—only in desperate situations can the complex facets of humanity be completely revealed. Mo Dexian, a minor employee at the Jinling Arsenal, lives a comfortable life in Gezhi Town due to his 'craftsman spirit,' but when the aggressors tighten the noose, he is the first to rise in rebellion—the flagpole hiding explosives serves as a metaphor, as he resolutely begins to fight. The captain of the artillery unit, Xiao Yan, who has always shown weakness and anxiety due to the psychological trauma of war, finally rises to become a true gunner who sacrifices himself beside his comrades. Picking up a kitchen knife, raising a firearm, drawing a bow, in Gezhi Town, there is no distinction between civilians and soldiers; nearly everyone is fighting. In the film, every owner of Gezhi Town is imperfect and has lovable or detestable flaws; most of the time they are ordinary and humble, only seeking to live their lives. Such character portrayal is actually more powerful; ordinariness is the norm, thus the extraordinary resistance and sacrifice is even more moving.

Strictly speaking, the victory logic of Gezhi Town appears overly simplistic. In contrast, the film’s portrayal of the enemy is largely caricatured. The Japanese soldiers are cruel, creating hell on earth, but how could they be that foolish? The various 'foolish' actions of enemies in the film are more to satisfy the audience’s pleasure, so a well-supplied Su Lu Tong cannon barely becomes a note of victory in battle. However, looking at it from another perspective, the victory logic of Gezhi Town is reasonable because it reflects the victory logic of the Chinese people in the War of Resistance. An individual's struggle may be powerless, a small town's struggle may be in vain, but the collective struggle of a continuously thriving great nation is full of strength. This is the most touching metaphor of “Gezhi Town.” #XiaoZhan

![[超话]](/images/weibo-emoji/超话.png) # (The author is the Vice Chairman of the Jiangsu Province Television Artists Association and a professor at Nanjing Normal University’s School of Journalism and Communication)

# (The author is the Vice Chairman of the Jiangsu Province Television Artists Association and a professor at Nanjing Normal University’s School of Journalism and Communication)

Baidu Entertainment Characters

2025-12-12 14:00:46+0800

#XiaoZhan![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # @肖战 @彭昱畅 @周依然6 'Gezhi Town' Interview: Xiao Zhan and @彭昱畅 showcase 'brotherly friendship' on site, Xiao Zhan and @周依然's Chongqing hometown buff stacking, the three reveal behind-the-scenes tidbits, who cried the most during the shoot? Plus, all three share New Year blessings, come check it out~⬇️#GezhiTown#

# @肖战 @彭昱畅 @周依然6 'Gezhi Town' Interview: Xiao Zhan and @彭昱畅 showcase 'brotherly friendship' on site, Xiao Zhan and @周依然's Chongqing hometown buff stacking, the three reveal behind-the-scenes tidbits, who cried the most during the shoot? Plus, all three share New Year blessings, come check it out~⬇️#GezhiTown#

![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # @肖战 @彭昱畅 @周依然6 'Gezhi Town' Interview: Xiao Zhan and @彭昱畅 showcase 'brotherly friendship' on site, Xiao Zhan and @周依然's Chongqing hometown buff stacking, the three reveal behind-the-scenes tidbits, who cried the most during the shoot? Plus, all three share New Year blessings, come check it out~⬇️#GezhiTown#

# @肖战 @彭昱畅 @周依然6 'Gezhi Town' Interview: Xiao Zhan and @彭昱畅 showcase 'brotherly friendship' on site, Xiao Zhan and @周依然's Chongqing hometown buff stacking, the three reveal behind-the-scenes tidbits, who cried the most during the shoot? Plus, all three share New Year blessings, come check it out~⬇️#GezhiTown#

Xinhua News Agency

2025-12-15 16:27:25+0800

#XiaoZhanSaysMillionsOfFamiliesMakeUsOneBigFamily# #GezhiTownCreativeInterview# '#XiaoZhanTalksAboutMoDexian'sProtectionAndGrowth#' Starring @肖战, the movie 'Gezhi Town' is now showing. A story of 'small families' during a turbulent era resonates with countless viewers. Xiao Zhan stated in an interview, 'As an actor, I replayed the scenes that Xiao Mo experienced in my mind from start to finish.' 'Protecting our own small family, the millions of small families, then forming our big family.' Click the video to step into 'Mo Dexian' and feel the determination and courage in protecting our homeland!

China Movie Report

2025-12-15 16:53:38+0800

#XiaoZhanSaysMoDexianOftenSeeksInternally# #PengYuchangSaysXiaoZhanCanTouchPeople'sHeartsWhenActing# The full interview with the creators of the movie 'Gezhi Town' is up! Xiao Zhan responds live to 'Mo Dexian, the hexagonal mechanic,' stating that he has viewed a lot of materials and observed the work state of mechanics. The biggest preparation was to contemplate Mo Dexian's emotional journey: 'Mo Dexian is not one to openly express negative emotions; many times he seeks inward.'

Talking about the collaboration with Xiao Zhan, Peng Yuchang mentioned 'As imagined, everyone gets in really quickly and is very in sync. Brother Zhan can really touch people's hearts during the shoot.' Zhou Yiran recalled a scene where she slapped Xiao Zhan, who joked, 'You slap so lightly, it's like you're caressing my face.' Xiao Zhan added, 'Sometimes, the person hitting is more nervous than the one being hit.' For more behind-the-scenes details about interactions with young actors and many improvised iconic scenes on set, click the video to unlock more content~

Talking about the collaboration with Xiao Zhan, Peng Yuchang mentioned 'As imagined, everyone gets in really quickly and is very in sync. Brother Zhan can really touch people's hearts during the shoot.' Zhou Yiran recalled a scene where she slapped Xiao Zhan, who joked, 'You slap so lightly, it's like you're caressing my face.' Xiao Zhan added, 'Sometimes, the person hitting is more nervous than the one being hit.' For more behind-the-scenes details about interactions with young actors and many improvised iconic scenes on set, click the video to unlock more content~

Global Times Entertainment

2025-12-16 12:57:35+0800

#XiaoZhanRespondsToThePremiereBeingEmotionalForTheAudience##XiaoZhan2025SummaryIsOngoing# #GlobalTimesInterviewWithXiaoZhan# 'Creative Team Speaks丨The movie "Gezhi Town" starring Xiao Zhan @肖战: Tracing Mo Dexian's Struggles and Growth' is written by Lan Xiaolong and directed by Kong Sheng, starring Xiao Zhan, Peng Yuchang, and Zhou Yiran, with the movie "Gezhi Town" @电影Gezhi Town released on December 6. The film focuses on ordinary people during the resistance war, telling the story of the blacksmith Mo Dexian (played by Xiao Zhan) who flees to Gezhi Town with his family amid the chaos of war, fighting against foreign enemies alongside the townspeople, transforming from 'protecting the small family' to 'defending the big family.' Recently, the lead actor Xiao Zhan accepted an interview with @环球时报 @环球时报文娱, sharing insights and growth from both inside and outside the play. What was his mood when he learned he would participate in "Gezhi Town"? Why was he so nervous that he couldn't sleep? What was the most important preparation for playing Mo Dexian? What is it like to portray a father? What thoughts did he have during the 'time travel' scene shooting? Which scenes left a lasting impact on him? Which audience feedback impressed him deeply? He also shares views on 'comfort zones', his reflections for 2025, and what he wants to say to those who support him, among other exciting content. Click on the video to hear Xiao Zhan narrate!

Fox Factory Great Interrogation

2025-12-17 10:30:31+0800

Fox Factory Great Interrogation ✖️ @肖战 The main feature is here! ![[赢牛奶]](/images/weibo-emoji/赢牛奶.png)

#XiaoZhanHasBeenWaitingForTheChongqingDialectScript# Xiao Zhan responded to fans saying he has a KPI of learning a local dialect for every drama he shoots, but it’s actually a coincidence; he has been waiting for the script in his local Chongqing dialect. Online calling out to all the teachers 🤓

#XiaoZhanSaidHeDoesNotHaveMoDexianLooseLips# Xiao Zhan talks about the contrast between Mo Dexian and himself, mainly that he doesn’t have as loose lips as Mo Dexian, precise in his output![[笑哈哈]](/images/weibo-emoji/笑哈哈.png)

This episode of 'Fox Factory Great Interrogation' is full of excitement, check the comments and follow on Sohu Video APP for benefits dropping ~ #GezhiTown#

![[赢牛奶]](/images/weibo-emoji/赢牛奶.png)

#XiaoZhanHasBeenWaitingForTheChongqingDialectScript# Xiao Zhan responded to fans saying he has a KPI of learning a local dialect for every drama he shoots, but it’s actually a coincidence; he has been waiting for the script in his local Chongqing dialect. Online calling out to all the teachers 🤓

#XiaoZhanSaidHeDoesNotHaveMoDexianLooseLips# Xiao Zhan talks about the contrast between Mo Dexian and himself, mainly that he doesn’t have as loose lips as Mo Dexian, precise in his output

![[笑哈哈]](/images/weibo-emoji/笑哈哈.png)

This episode of 'Fox Factory Great Interrogation' is full of excitement, check the comments and follow on Sohu Video APP for benefits dropping ~ #GezhiTown#

Gezhi Town

2025-12-17 12:00:02+0800

#GezhiTown![[超话]](/images/weibo-emoji/超话.png) # #XiaoZhanMoDexianCrossTimeDialogue# A phrase 'Generously risk death' connects the perseverance amidst the smoke of war; a call 'Did you see?' crosses time to respond to expectations. The creators' resonance with their on-screen counterparts is a heartfelt tribute to the unknown resistance fighters and a reminder to cherish the current peaceful life.

# #XiaoZhanMoDexianCrossTimeDialogue# A phrase 'Generously risk death' connects the perseverance amidst the smoke of war; a call 'Did you see?' crosses time to respond to expectations. The creators' resonance with their on-screen counterparts is a heartfelt tribute to the unknown resistance fighters and a reminder to cherish the current peaceful life.

#GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in theaters.

![[超话]](/images/weibo-emoji/超话.png) # #XiaoZhanMoDexianCrossTimeDialogue# A phrase 'Generously risk death' connects the perseverance amidst the smoke of war; a call 'Did you see?' crosses time to respond to expectations. The creators' resonance with their on-screen counterparts is a heartfelt tribute to the unknown resistance fighters and a reminder to cherish the current peaceful life.

# #XiaoZhanMoDexianCrossTimeDialogue# A phrase 'Generously risk death' connects the perseverance amidst the smoke of war; a call 'Did you see?' crosses time to respond to expectations. The creators' resonance with their on-screen counterparts is a heartfelt tribute to the unknown resistance fighters and a reminder to cherish the current peaceful life.#GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in theaters.

Guangming Daily

2025-12-17 18:45:14+0800

#XiaoZhanPracticingLinesUntilForgettingItIsADialect# #GuangmingDailyInterviewWithXiaoZhan# Recently, the movie "Gezhi Town" is currently showing. The actor @肖战, who plays Mo Dexian in the film, mentioned during an interview with Guangming Daily that the hardest part during the performance is the lines. Sometimes he practices a line many times until he forgets it is in a dialect and can say it fluently. (Reported by Wu Yaqi and Xing Yanyan)

Gezhi Town

2025-12-18 13:00:01+0800

#GezhiTown![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToUnlockMoreDetails# The film is exquisitely produced, with thoughtful details in every frame! The couplets of Yichang and Gezhi Town, Mo Dexian's flagpole bomb... have you noticed these hidden clues in the details?

# #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToUnlockMoreDetails# The film is exquisitely produced, with thoughtful details in every frame! The couplets of Yichang and Gezhi Town, Mo Dexian's flagpole bomb... have you noticed these hidden clues in the details?

#GezhiTown# is currently showing, see you in theaters.

![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToUnlockMoreDetails# The film is exquisitely produced, with thoughtful details in every frame! The couplets of Yichang and Gezhi Town, Mo Dexian's flagpole bomb... have you noticed these hidden clues in the details?

# #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToUnlockMoreDetails# The film is exquisitely produced, with thoughtful details in every frame! The couplets of Yichang and Gezhi Town, Mo Dexian's flagpole bomb... have you noticed these hidden clues in the details?#GezhiTown# is currently showing, see you in theaters.

Gezhi Town

2025-12-18 14:00:01+0800

#GezhiTown![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToUnlockMoreDetails# Xiao Mo @肖战 is here to remind you to dig into the details! The items taken out by Tai Ye in the ruins, the wall of the Mo family that didn’t fall, Mo Dexian's fantasies… Did you notice these little details?

# #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToUnlockMoreDetails# Xiao Mo @肖战 is here to remind you to dig into the details! The items taken out by Tai Ye in the ruins, the wall of the Mo family that didn’t fall, Mo Dexian's fantasies… Did you notice these little details?

#GezhiTown# is currently in theaters, see you in the cinema.

![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToUnlockMoreDetails# Xiao Mo @肖战 is here to remind you to dig into the details! The items taken out by Tai Ye in the ruins, the wall of the Mo family that didn’t fall, Mo Dexian's fantasies… Did you notice these little details?

# #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToUnlockMoreDetails# Xiao Mo @肖战 is here to remind you to dig into the details! The items taken out by Tai Ye in the ruins, the wall of the Mo family that didn’t fall, Mo Dexian's fantasies… Did you notice these little details?#GezhiTown# is currently in theaters, see you in the cinema.

Guangming Daily

2025-12-18 14:30:01+0800

'#XiaoZhanSaysManyStoriesBeyondTheScreen#' #GuangmingDailyExclusiveInterviewXiaoZhan# Actor @肖战, who plays Mo Dexian in the movie 'Gezhi Town', discussed in an interview that the 'tears' in the film often stem from various stimuli and feelings in the moment. The scene that left the deepest impression on him was a monologue with his family under a pillar. He recalled the shooting scene and expressed that many stories are actually beyond the screen. (Guangming Daily multimedia reporters Wu Yaqi and Xing Yanyan)

Gezhi Town

2025-12-19 20:00:03+0800

#GezhiTown![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #TenThousandLightsAreTheBestEasterEggOfGezhiTown# The movie concludes, and the countless lights outside are the best easter egg of this story. In today's prosperous scenery, the people of Gezhi Town have all seen it.

# #TenThousandLightsAreTheBestEasterEggOfGezhiTown# The movie concludes, and the countless lights outside are the best easter egg of this story. In today's prosperous scenery, the people of Gezhi Town have all seen it.

#GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in theaters.

![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #TenThousandLightsAreTheBestEasterEggOfGezhiTown# The movie concludes, and the countless lights outside are the best easter egg of this story. In today's prosperous scenery, the people of Gezhi Town have all seen it.

# #TenThousandLightsAreTheBestEasterEggOfGezhiTown# The movie concludes, and the countless lights outside are the best easter egg of this story. In today's prosperous scenery, the people of Gezhi Town have all seen it.#GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in theaters.

Guangming Daily

2025-12-19 16:57:14+0800

'#XiaoZhanSaysTheMeaningOfBeingAnActor#' #GuangmingDailyExclusiveInterviewXiaoZhan# Actor @肖战 spoke in a conversation with Guangming Daily reporters about the film 'Gezhi Town', which focuses on small characters and conveys a larger theme. Everyone will have their own feelings after watching it. Xiao Zhan remarked that hearing a father share his thoughts and emotions about the father character in the film during the premiere made him feel that what he is doing is meaningful. (Reporters Wu Yaqi and Xing Yanyan)

Gezhi Town

2025-12-20 11:00:01+0800

#GezhiTown![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownOverseasRelease#

# #GezhiTownOverseasRelease#

Transforming craftsmanship into a weapon, building a homeland with our own hands.

Machinist Mo Dexian @肖战 invites you to witness a different story of the people's resistance against Japan.

#GezhiTown# is set to be released in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and North America soon. Looking forward to seeing you on the big screen!

![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownOverseasRelease#

# #GezhiTownOverseasRelease# Transforming craftsmanship into a weapon, building a homeland with our own hands.

Machinist Mo Dexian @肖战 invites you to witness a different story of the people's resistance against Japan.

#GezhiTown# is set to be released in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, and North America soon. Looking forward to seeing you on the big screen!

Gezhi Town

2025-12-22 12:00:01+0800

#GezhiTown![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownPostScreeningInteraction# @肖战 has thrown out five viewing questions that hide the film's craftsmanship in 'Gezhi Town'! Those who have watched it come to the comments section to answer~

# #GezhiTownPostScreeningInteraction# @肖战 has thrown out five viewing questions that hide the film's craftsmanship in 'Gezhi Town'! Those who have watched it come to the comments section to answer~

#GezhiTown# is now in theaters, see you at the cinema.

![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownPostScreeningInteraction# @肖战 has thrown out five viewing questions that hide the film's craftsmanship in 'Gezhi Town'! Those who have watched it come to the comments section to answer~

# #GezhiTownPostScreeningInteraction# @肖战 has thrown out five viewing questions that hide the film's craftsmanship in 'Gezhi Town'! Those who have watched it come to the comments section to answer~#GezhiTown# is now in theaters, see you at the cinema.

Gezhi Town

2025-12-23 11:00:01+0800

#GezhiTown![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToAnswerQuestions# The film is filled with many plots and hidden meanings. Mo Dexian @肖战 has left a puzzle, inviting you to unveil it together.

# #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToAnswerQuestions# The film is filled with many plots and hidden meanings. Mo Dexian @肖战 has left a puzzle, inviting you to unveil it together.

#GezhiTown# is currently in theaters, see you there.

![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToAnswerQuestions# The film is filled with many plots and hidden meanings. Mo Dexian @肖战 has left a puzzle, inviting you to unveil it together.

# #GezhiTownXiaoZhanInvitesYouToAnswerQuestions# The film is filled with many plots and hidden meanings. Mo Dexian @肖战 has left a puzzle, inviting you to unveil it together.#GezhiTown# is currently in theaters, see you there.

Global Times Entertainment

2025-12-23 06:50:02+0800

#XiaoZhanTalksAboutMoDexian'sStrugglesAndResistance# #XiaoZhanSaysNeverThoughtOfDistinguishingComfortZone# 'Full Interview 👉 Creative Talk | Movie《Gezhi Town》starring Xiao Zhan @肖战: “得闲 is longing for peace, 准制 is resilience in adversity”' Written by Lan Xiaolong, directed by Kong Sheng, produced by Hou Hongliang, starring Xiao Zhan, Peng Yuchang, and Zhou Yiran. The movie @电影得闲谨制 officially releases on December 6. Recently, lead actor Xiao Zhan accepted an exclusive interview with 'Global Times' @环球时报 @环球时报文娱, discussing his understanding of the character and filming insights, sharing his views on external evaluations and his attitude towards acting. 'In the process of filming and working, my thoughts are very simple; I just want to do my best. Whether I can do it is a question of ability, but wanting to do it well is a question of my attitude.' said Xiao Zhan.

In the early part of the film, Mo Dexian appears to be revolving around his own 'little home', just having comforted his elderly grandfather and then turning to educate his mischievous son. In his spare time, he manages to listen to the radio and uses his skills as a handyman to repair various tools. In Xiao Zhan's eyes, Mo Dexian is not a conventional hero; he is 'nervous' and 'disorganized', and at times, he is a bit of a 'chatterbox'. He experiences struggles and growth under external stimuli. Xiao Zhan admits that collaborating with director Kong Sheng and screenwriter Lan Xiaolong, as well as playing such a unique character, made him initially so nervous that he experienced insomnia. To portray 得闲 well, Xiao Zhan focused not on acting methods, but on returning to the character's 'background'.

After the release of 《Gezhi Town》, the behind-the-scenes footage of Mo Dexian venting his anger at the mountaintop sparked discussions on social media, with netizens expressing that peaceful living is hard-earned. While filming, Xiao Zhan was actually facing towering skyscrapers and modern overpasses, yet he needed to portray 得闲's suppressed and painful state under the shadow of war. This strong 'temporal and spatial overlap' left him unable to withdraw from the character for a long time after filming. Now, there are many interpretations of the details about 《Gezhi Town》 on social media, and the film's dark humor narrative and the stories of ordinary people's resistance leave the audience with an emotional 'aftertaste.' Xiao Zhan also gained new insights into the work after watching it, recalling a touching conversation during the premiere that brought him to the brink of tears.

Why was Xiao Zhan chosen to play Mo Dexian? The movie's executive producer Hou Hongliang stated in an interview that he sees in Xiao Zhan the attitude of an actor stepping out of the 'comfort zone.' Xiao Zhan is grateful for this evaluation, but he believes he has never thought of 'stepping out or going somewhere,' only wanting to maintain the most positive attitude and do his best in every job. In 2025, Xiao Zhan will meet the audience with multiple works. As this interview approached the end of the year, when asked about his reflection on 2025, Xiao Zhan shyly said he is 'quite afraid of reflection and expectations...' Click below to unlock the full interview~

In the early part of the film, Mo Dexian appears to be revolving around his own 'little home', just having comforted his elderly grandfather and then turning to educate his mischievous son. In his spare time, he manages to listen to the radio and uses his skills as a handyman to repair various tools. In Xiao Zhan's eyes, Mo Dexian is not a conventional hero; he is 'nervous' and 'disorganized', and at times, he is a bit of a 'chatterbox'. He experiences struggles and growth under external stimuli. Xiao Zhan admits that collaborating with director Kong Sheng and screenwriter Lan Xiaolong, as well as playing such a unique character, made him initially so nervous that he experienced insomnia. To portray 得闲 well, Xiao Zhan focused not on acting methods, but on returning to the character's 'background'.

After the release of 《Gezhi Town》, the behind-the-scenes footage of Mo Dexian venting his anger at the mountaintop sparked discussions on social media, with netizens expressing that peaceful living is hard-earned. While filming, Xiao Zhan was actually facing towering skyscrapers and modern overpasses, yet he needed to portray 得闲's suppressed and painful state under the shadow of war. This strong 'temporal and spatial overlap' left him unable to withdraw from the character for a long time after filming. Now, there are many interpretations of the details about 《Gezhi Town》 on social media, and the film's dark humor narrative and the stories of ordinary people's resistance leave the audience with an emotional 'aftertaste.' Xiao Zhan also gained new insights into the work after watching it, recalling a touching conversation during the premiere that brought him to the brink of tears.

Why was Xiao Zhan chosen to play Mo Dexian? The movie's executive producer Hou Hongliang stated in an interview that he sees in Xiao Zhan the attitude of an actor stepping out of the 'comfort zone.' Xiao Zhan is grateful for this evaluation, but he believes he has never thought of 'stepping out or going somewhere,' only wanting to maintain the most positive attitude and do his best in every job. In 2025, Xiao Zhan will meet the audience with multiple works. As this interview approached the end of the year, when asked about his reflection on 2025, Xiao Zhan shyly said he is 'quite afraid of reflection and expectations...' Click below to unlock the full interview~

Fox Factory Great Interrogation

2025-12-25 19:00:11+0800

Fox Factory Big Question ✖️ @肖战 Interaction ① Coming! ![[赢牛奶]](/images/weibo-emoji/赢牛奶.png)

#XiaoZhanSaysMoDexianDoesYourBest# When asked who in 《Gezhi Town》 most embodies 'doing your best,' Xiao Zhan replied, isn't that Xiao Mo? There’s always unfinished business![[开学季]](/images/weibo-emoji/开学季.png)

#XiaoZhanGivesAnEpicResponse# Xiao Zhan online gave grandpa a '夯爆了.' He truly is our top lucky charm![[哈哈]](/images/weibo-emoji/哈哈.png) #GezhiTown#

#GezhiTown#

![[赢牛奶]](/images/weibo-emoji/赢牛奶.png)

#XiaoZhanSaysMoDexianDoesYourBest# When asked who in 《Gezhi Town》 most embodies 'doing your best,' Xiao Zhan replied, isn't that Xiao Mo? There’s always unfinished business

![[开学季]](/images/weibo-emoji/开学季.png)

#XiaoZhanGivesAnEpicResponse# Xiao Zhan online gave grandpa a '夯爆了.' He truly is our top lucky charm

![[哈哈]](/images/weibo-emoji/哈哈.png) #GezhiTown#

#GezhiTown#

Fox Factory Great Interrogation

2025-12-26 14:00:05+0800

Fox Factory Big Interrogation ✖️ @肖战 Interaction 2 is here! ![[赢牛奶]](/images/weibo-emoji/赢牛奶.png)

#XiaoZhanReallyLikesAudienceInterpretations# Xiao Zhan said he particularly enjoys watching interpretations from audience friends, which are very interesting, and some even surprised him during filming![[思考]](/images/weibo-emoji/思考.png)

#XiaoZhanRevealsGezhiTownFirstAppearance# Fun fact: What was Mo Dexian doing during his first appearance? Xiao Zhan talks online about Su Luotong clapping on stage; this black-and-white scene has no plot, and it should be a little Easter egg from the director for the character![[送花花]](/images/weibo-emoji/送花花.png) #GezhiTown#

#GezhiTown#

![[赢牛奶]](/images/weibo-emoji/赢牛奶.png)

#XiaoZhanReallyLikesAudienceInterpretations# Xiao Zhan said he particularly enjoys watching interpretations from audience friends, which are very interesting, and some even surprised him during filming

![[思考]](/images/weibo-emoji/思考.png)

#XiaoZhanRevealsGezhiTownFirstAppearance# Fun fact: What was Mo Dexian doing during his first appearance? Xiao Zhan talks online about Su Luotong clapping on stage; this black-and-white scene has no plot, and it should be a little Easter egg from the director for the character

![[送花花]](/images/weibo-emoji/送花花.png) #GezhiTown#

#GezhiTown#

Guangming Daily

2025-12-26 18:00:01+0800

‘#XiaoZhanSaidHeLikesMoDexian#’#TurnsOutXiaoZhanThinksSoDeeply# Recently, actor @肖战 shared his experiences and feelings of playing Mo Dexian in the movie 'Gezhi Town' during an exclusive interview with Guangming Daily. How to understand and grasp the character? What was the biggest challenge during the filming process? What was the most impressive scene? What kind of growth and insights has he gained? The complete video is presented, listen to Xiao Zhan's series of thoughts and reflections. (Guangming Daily multimedia reporters Wu Yaqi, Xing Yanyan) #GuangmingDailyExclusiveInterviewXiaoZhan#

Fox Studio Big Interrogation

2025-12-27 14:00:02+0800

Fox Studio Big Interrogation ✖️ @肖战 Interaction 3 is here! ![[赢牛奶]](/images/weibo-emoji/赢牛奶.png)

#XiaoZhanLikesTheMemeILoveMyself# Xiao Zhan is online for the question 'Why is it 'Myself'?' 🦊 Here’s the answer: 'I am the best person for myself.' Xiao Zhan says this is great, and we should learn from such people, feeling worthy![[打call]](/images/weibo-emoji/打call.png)

#XiaoZhanSaidLovingYourselfIsBeingGoodToYourself# Xiao Zhan appreciates the current state of mind of young people and believes we should learn from those younger than him. He thinks worthiness means 'I am valuable.' Everyone's charm shines in their fields of expertise and passion![[点赞]](/images/weibo-emoji/点赞.png) #GezhiTown#

#GezhiTown#

![[赢牛奶]](/images/weibo-emoji/赢牛奶.png)

#XiaoZhanLikesTheMemeILoveMyself# Xiao Zhan is online for the question 'Why is it 'Myself'?' 🦊 Here’s the answer: 'I am the best person for myself.' Xiao Zhan says this is great, and we should learn from such people, feeling worthy

![[打call]](/images/weibo-emoji/打call.png)

#XiaoZhanSaidLovingYourselfIsBeingGoodToYourself# Xiao Zhan appreciates the current state of mind of young people and believes we should learn from those younger than him. He thinks worthiness means 'I am valuable.' Everyone's charm shines in their fields of expertise and passion

![[点赞]](/images/weibo-emoji/点赞.png) #GezhiTown#

#GezhiTown#

Gezhi Town

2025-12-29 14:00:01+0800

#GezhiTown![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #XiaoZhanAndMoDexianCrossTemporalDialogue# In 2025, @肖战 sends a cross-temporal video message to Mo Dexian: The common people are now living a 'Dexian' life, and the whole world is using 'Made in China'. What our ancestors once desired has now been fulfilled.

# #XiaoZhanAndMoDexianCrossTemporalDialogue# In 2025, @肖战 sends a cross-temporal video message to Mo Dexian: The common people are now living a 'Dexian' life, and the whole world is using 'Made in China'. What our ancestors once desired has now been fulfilled.

#GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in the theater.

![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #XiaoZhanAndMoDexianCrossTemporalDialogue# In 2025, @肖战 sends a cross-temporal video message to Mo Dexian: The common people are now living a 'Dexian' life, and the whole world is using 'Made in China'. What our ancestors once desired has now been fulfilled.

# #XiaoZhanAndMoDexianCrossTemporalDialogue# In 2025, @肖战 sends a cross-temporal video message to Mo Dexian: The common people are now living a 'Dexian' life, and the whole world is using 'Made in China'. What our ancestors once desired has now been fulfilled.#GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in the theater.

Gezhi Town

2025-12-31 20:00:01+0800

#GezhiTown![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownMovedAFatherDeeply# A father deeply empathized after watching the film, saying 'Xiao Zhan portrayed the most instinctive impulse of fatherly love.' Fear is human nature, but using one's body to build a wall for family is a fearless love granted by that emotion.

# #GezhiTownMovedAFatherDeeply# A father deeply empathized after watching the film, saying 'Xiao Zhan portrayed the most instinctive impulse of fatherly love.' Fear is human nature, but using one's body to build a wall for family is a fearless love granted by that emotion.

#GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in the theater.

![[SuperTopic]](/images/weibo-emoji/SuperTopic.png) # #GezhiTownMovedAFatherDeeply# A father deeply empathized after watching the film, saying 'Xiao Zhan portrayed the most instinctive impulse of fatherly love.' Fear is human nature, but using one's body to build a wall for family is a fearless love granted by that emotion.

# #GezhiTownMovedAFatherDeeply# A father deeply empathized after watching the film, saying 'Xiao Zhan portrayed the most instinctive impulse of fatherly love.' Fear is human nature, but using one's body to build a wall for family is a fearless love granted by that emotion.#GezhiTown# is now showing, see you in the theater.

CCTV News

2025-12-08 20:30:26+0800

#XiaoZhanGentleMessage2026# '#XiaoZhan'sBlessingsFor2026#![[心]](/images/weibo-emoji/心.png) ' The year 2025 is coming to an end, and actor @肖战 invites you to embrace the new year: 'Count the moments with me in words. In the new year, every day deserves to be opened with care. May we have peace and longevity, and meet often.' In 2026, let's grow towards the sun together!

' The year 2025 is coming to an end, and actor @肖战 invites you to embrace the new year: 'Count the moments with me in words. In the new year, every day deserves to be opened with care. May we have peace and longevity, and meet often.' In 2026, let's grow towards the sun together!

![[心]](/images/weibo-emoji/心.png) ' The year 2025 is coming to an end, and actor @肖战 invites you to embrace the new year: 'Count the moments with me in words. In the new year, every day deserves to be opened with care. May we have peace and longevity, and meet often.' In 2026, let's grow towards the sun together!

' The year 2025 is coming to an end, and actor @肖战 invites you to embrace the new year: 'Count the moments with me in words. In the new year, every day deserves to be opened with care. May we have peace and longevity, and meet often.' In 2026, let's grow towards the sun together!